《龙猫》:成年人不奔跑

上周末去影院看了《龙猫》。

按理来说,我应该已经跟故事里的父亲年纪相仿了,但是以我的人生阅历,还很难主动带入到他的视角。 而我离童年就更加遥远了,自然也不可能像两姐妹那样天真地感受这个世界。 结果就是我像一个介乎父女两代人之间的旁观者,和电影的创作者一起追忆逝去的纯真时光。

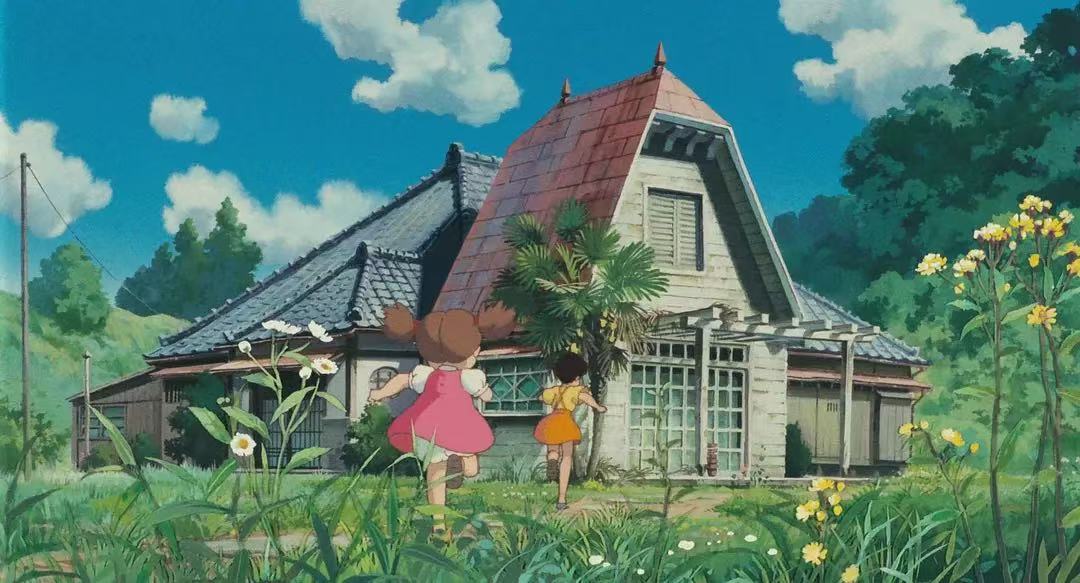

电影一开始,因为母亲生病住院,12岁的皋月和4岁的梅跟随父亲搬到了医院附近的乡下居住。 给我的第一印象就是,她俩就像两台永动机,永远在奔跑,永远在大叫。 包括到后来,龙猫也和小梅比赛尖叫,猫巴士像风一样奔跑。

大概今年年初的时候,有一天我突然意识到,办公室里的同事不管遇到多棘手的问题,表面看起来也还是慢悠悠地走来走去,而我好像动不动就会双脚离地小跑起来。 这可能是因为我本来性子就比较急,一有什么任务就很焦虑,想要赶紧把事情做完,最终外化成了小跑。 但其实不管跑或不跑,对最终什么时候能解决问题并没有太大影响。甚至因为我一直保持神经紧张的状态,反而会犯一些低级错误。 所以当时就想出这一句“成年人不奔跑”,一旦想要跑起来的时候就提醒自己,放轻松。

当然,电影里两姐妹的跑和尖叫,是生命力的自然迸发,和我这种被资本主义压榨出来的焦虑是不一样的,但都是成年世界的对立面。

随着故事发展,两姐妹遇到了龙猫。 电影里第一次让我鼻酸想要落泪的瞬间,是在一个深夜,两姐妹和龙猫们一起在播撒了橡树种子的草地前拜拜。 久石让宏大空灵的配乐响起,橡树苗破土而出,像喷泉一样涌向天空,长成一棵参天大树。

回来在 b站看到一个剧情分析 ,我才注意到这一幕的画面左下角,是爸爸在暖黄的灯光下伏案工作。Up主说龙猫来源于姐妹的想象,大中小三只龙猫就对应着爸爸、姐姐和小梅。 “只有小孩能看见龙猫,只有大人可以成为龙猫”。 讲得真好啊。而我现在介乎于小孩和大人之间,所以才会生出一方面怀旧,另一方面又充满希望的感受吧。

Last weekend, I went to the theater to watch My Neighbor Totoro.

Technically, I’m probably around the same age now as the father in the story. But with the life experience I have, it’s still hard to fully put myself in his shoes. And childhood feels even farther away — so I can’t really see the world with the same wide-eyed wonder as the two sisters either. So I ended up watching the film as a kind of in-between — not quite a parent, not quite a child — just a quiet observer. Together with the creators, I felt like I was gently revisiting a long-lost sense of innocence.

The story opens with 12-year-old Satsuki and 4-year-old Mei moving to the countryside with their father, to be closer to the hospital where their mother is being treated. My first impression was: these two are perpetual motion machines. Always running. Always yelling. Later on, even Totoro joins in — roaring alongside Mei, and the cat bus races through the fields like the wind.

Earlier this year, I had a moment at work where I realized something. No matter how stressful things got, my coworkers always seemed to walk calmly from one place to another. Meanwhile, I was the only one literally half-jogging down the hallway. Maybe it’s just my personality — I tend to get anxious as soon as a task comes in, and I want to get it done now. That anxiety leaks out into how I move: rushed, urgent, slightly frantic. But the truth is, running doesn’t really help. It doesn’t get the problem solved any faster. If anything, being in a constant state of tension just leads to careless mistakes. So I came up with this little reminder: “Adults don’t run.” Whenever I feel like sprinting through the office, I tell myself: slow down. Breathe.

Of course, the running and yelling of the two sisters in Totoro is something else entirely — it’s raw, joyful energy. It’s life bursting at the seams. Whereas mine is just anxiety, shaped by capitalism. But in their own way, both are the opposite of what it means to be a “functioning adult.”

As the story unfolds, the sisters meet Totoro. The first moment that made me tear up came late one night, when they’re standing with Totoro in a field where they planted acorns. They bow together, the wind picks up, and Joe Hisaishi’s sweeping score starts to play. Suddenly, the seeds sprout, then shoot up into the sky like a fountain, becoming a towering tree.

Later, I came across this video on Bilibili, which pointed out something I hadn’t noticed before: in the bottom left corner of that scene, the girls’ father is shown quietly working under the warm glow of his desk lamp. The creator of the video suggested that the three Totoros represent the father, Satsuki, and Mei — and that Totoro is a projection of their imagination. “Only children can see Totoro,” they said, “but only adults can become Totoro.” What a beautiful thought.

And maybe that’s exactly why the film hit me so deeply — because right now, I’m somewhere in between. Not quite a child anymore, not yet a full-grown Totoro. Nostalgic for what’s gone, but still quietly hopeful for what’s to come.

👁️ 0 views